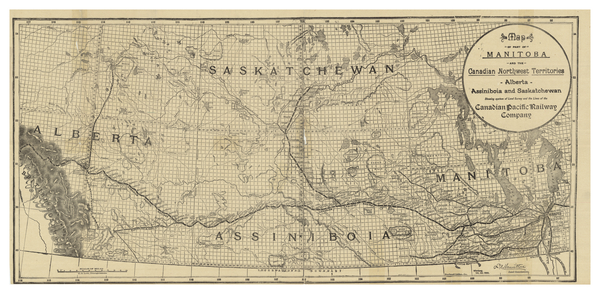

The 1885 Rebellion is sometimes known as the North-West Rebellion and was the first combat action of the Canadian army. The causes of the North-West Rebellion were varied but generally were caused by the rapid expansion of Canadian authority westward during the later half of the 19th Century. This page will assess the cause of the rebellion by dividing the causes into three separate ethno-cultural groups: The Metis, First Nations, and Settlers.

The Metis

The causes of the rebellion for many Metis stemmed from the aftermath of the Red River Resistance in 1870. In 1870, Canada had purchased ‘Ruperts Land’ from the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) with the support of the British Government. The between the early 1600s and 1870, the Hudson’s Bay Company and their rival the North West Company had set up a series of trading forts throughout the North West to trade with local indigenous populations. In 1821 the two trading companies would merge while retaining the Hudson’s Bay Company name. Over time, business ties turned to family ties as fur traders and local indigenous populations intermixed and intermarried. The children of these families were known as the Metis or Country Born and represented an entirely new hybrid culture. Marriage between a Hudson’s Bay Company trader and indigenous peoples was forbidden by company policy so the families resulting from these relationships often lived beside but not within the forts themselves. Most traders who worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company were themselves indentured servants who were forced to follow the whims of the company. Often traders would be moved between forts over the course of their service with the Hudson’s Bay Company with their now transplanted families following them across the country forming new hybrid communities outside the various forts. At the end of the trader’s term the Hudson’s Bay Company often forced the trader to return to Europe leaving their transplanted families isolated and alone. Many families that were now without a patriarch would stay around the forts or move to the Red River settlement outside of Fort Gary.

The communities that formed around these forts became home to the Metis peoples and were a place where a separate Metis identity was formed. The children of former or current traders would find jobs as boatmen, hunters, or guides, with the women cooking and preparing furs for the fort. To supply the fort with food many of these Metis’ groups would farm and hunt buffalo to sell to the fort to support themselves. Metis farms were organized often along long thin segments of land connected to a water way using a copy of the French seignorial system.

In 1870, Canada sought to exert control over the Red River Settlement after purchasing the rights to the North West from the Hudson’s Bay Company. Conflict would spring up between the Metis and the Canadian government over land use and ownership. William MacDougall, who was assigned to be Canadian Lt. Governor of the colony, implemented the square concession-based land system used throughout English Canada. This system would be overlayed on top of the existing and occupied seignorial farms dividing up the farms and lands of the Metis for purchase by new European settlers. Under this land use system waterfront property would be reserved for the most expensive plots of land.

The Canadian government under Sir John A. MacDonald sought to expand settlement into the North West rapidly and chose to treat the new land area as a federally administered territory rather than as a new province with its own responsible government. As a territory the wealth of the land could be directed to support the Federal government – a government that was running low on money. Conflict over land rights, language rights, and religious rights, would lead the Metis under the leadership of Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont to seize and occupy Fort Gary (in modern day Winnipeg) from the retreating Hudson’s Bay Company to form their own provisional government which would negotiate with the Canadian government the area’s entry into Canada as a unique province. It was at this time a rebellious group of settlers from Ontario (members of the Orange Order) would attempt to overthrow the Metis provisional government which would lead to the arrest and later execution of Thomas Scott. The execution of Thomas Scott would polarize the populations of Ontario and Quebec with those in Ontario seeking restitution and the overthrow of Riel’s government through violence, while those in Quebec saw the French speaking, and Catholic, Metis as simply protecting their own rights against English aggression. The execution of Scott would play a major role in the mobilization of the Canadian population fifteen years later during the 1885 Rebellion.

Without a way to quickly send a military force to the area, McDonald was forced to negotiate. McDonald agreed to allow the Metis dominated Red River Colony to enter Canada as the province of Manitoba. French language, catholic services, and Metis culture would be protected. Metis family heads would be provided with script (a coupon of sorts) for a parcel of land. It was assumed by many Metis that this land would be their current land already under current cultivation. The McDonald government would not allow Manitoba to control its own natural resources – these would be controlled federally and benefit the federal government. In secret, a military expedition was sent from Ontario under the command of Colonel Wolseley, but they would have to travel overland through hundreds of kilometers of thick bush. Wolseley (the last British officer to command an action in Canada) was tasked with arresting Riel and Dumont for the murder of Scott.

When the Wolseley expedition arrived in Manitoba, most of the Metis men were away on their traditional buffalo hunt. Word was given to many of the leaders of the provisional government to fee before they were arrested. Many fled either into the United States or deeper into the North West into what would become Alberta and Saskatchewan. Angry at their inability to capture the leaders of the Metis resistance some Canadian troops harassed Metis families and burned farms. Overtime, as more newcomers arrived in Manitoba, land use issues sprung up again. Many Metis were saddened to find that their script could not be used for their existing seignorial farms and could only be used for a farm in the new concession system. Without the leadership of their elected provincial government leaders like Riel (who was now the Premier of the province but was also in hiding), the Metis struggled to stand up for the awarded rights. Corrupt land agents sold the now divided river front lots of the Metis for high prices to newcomers and evicted families were forced to either cash in their script for money or accept less desirable new lands. In short order, Manitoba would become dominated by thousands of new English-speaking settlers who would use their larger population to roll back language and cultural rights that the Metis had negotiated under Riel. Thousands of Metis would abandon their lands and move further inland and out of the jurisdiction of Manitoba setting up new communities and farms further west.

Eventually the same problems that Metis communities faced in Manitoba followed them west. Much of the railway that Canada was building would be paid for in land grants to the company building the railway. The railway could select sections of land to sell to newcomers to raise needed funds for construction. The railway often looked to sell land that was water adjacent, and these lands were at time occupied (illegally according to the Canadian government) by Metis settlers. New settlers to the area purchased or were provide deed for farmland that was already occupied by existing Metis communities. When the Metis appealed to the Canadian government, the government leaders replied that the Metis held no ownership deed for the land. Canadian officials also argued that the “script” that Metis people had received in Manitoba only applied to lands in Manitoba and that the script were forfeit when Metis families left the province.

First Nations

It was the National Policy of Prime Minister Sir John A. McDonald and Canada to see Canada’s prairies settled by immigrants to exert / cement control over the lands and to deter any American attempts at annexation /expansion. Thousands of new settlers would move to what was at the time the North West Territories. Here land could be had for free if newcomers agreed to live on the land for at least 2 years and bring a certain acreage under cultivation. The building of the Canadian Pacific Railroad would open the area to future setters.

To support the expansion of the railway and settlement, new peace and land treaties were signed with First Nation’s along the proposed route. These treaties were to follow the guidelines set forth in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 which stated that all treaties with First Nations had to be negotiated on a nation-to-nation basis. Many First Nations were aware of the bloody conflicts that other indigenous groups were facing in the United States and wanted to avoid direct conflict with the Canadians. The Canadian government was also aware of the conflicts in the USA and wanted to avoid the cost of a massive frontier war. The massacre of General Custer at Little Big Horn was seared into the minds of everyone in the West. Thus, Treaties were negotiated between the Crown and First Nations. Recent scholarship has highlighted that there were issues with translations and understanding between government representatives and First Nations. Many of the promises that the Canadian government had made were also overly vague. Many First Nation’s leaders were angered by the fact that the government had not been forthcoming with the support that they believed that they had negotiated for when the herds of buffalo that were a primary food source for many plains people began to decline.

In the United States, to force indigenous peoples to sign treaties (and hopefully end an era of bloody conflict), an attempt was made to destroy the buffalo herds and deprive indigenous peoples of their food sources. Since the great buffalo herds were transnational the elimination of the buffalo in the United States greatly affected Canada’s indigenous peoples. Many First Nations were angered by the meager rations that were provided by the Canadian government which had promised to provide food in times of famine as stated in their Treaties. Rations that were provided were minimal, sometimes rotten, and not varied, the government feared that enhanced rations would provide dependence and instead the Federal Government pursued a policy using their unilateral powers under the Indian Act of 1876 to “encouraged” plains groups to engage in their own agriculture. As part of this the Canadian government would fund industrial schools throughout the region that would teach First Nations children agricultural skills. These schools, run by government sanctioned churches, would force First Nation’s children into what were at times abusive situations. Although this policy may heave seemed sound to leaders in Ottawa it ignored the geographic realities on the ground with most First Nations being forced to live in the less fertile areas of the territories which would lead to agricultural struggles. Thus, starvation and a meager Canadian response had left many First Nation’s starving, desperate and distrustful of the Crown.

Settlers

Many European settlers would also come to the North West in order to farm during this time period. Many of these settlers had speculated or chosen farms that they felt would be close to the proposed route of the new railway. Lands close to the railway were seen as more valuable due to the easy of access to markets and proximity to towns and stores that would be set up along the route. In the 1880s, the Canadian government and the CPR decided on a new route for the railway which would go further south than originally planned. This change was influenced by the railway wanting to limit American economic influence and the discovery of coal in what is now Lethbridge Alberta. This left many settlers hundreds of kilometers away from the railway in lands that were now less valuable. Many settlers were angered that the Canadian government supported this change. The fact that there was no representative government for the North West at the time meant that there was little settlers could do to voice their anger.

Rebellion

With nearly the entire North West angry for a variety of reasons, the time was right for a rebellion. The Metis of the North West and many of the new settlers believed that Louis Riel could once again be their salvation. It was hoped that through repeating the process of the Red River Resistance, that the North West could gain control of their lands and resources and see the set up of a proper responsible government that would represent their needs. Dumont travelled to Montana to find and repatriate Riel so that he could become the symbolic head of the movement and their movement’s political leader. Riel had changed since 1870 and had been hospitalize for psychiatric issues. Riel agreed to return to lead the rebellion but also believed that his mission had become divine. He believed that it was god’s will set up a new church and Vatican in the Canadian prairies – this controversial religious mission would contribute to the rebellion losing support from the largely Catholic province of Quebec.

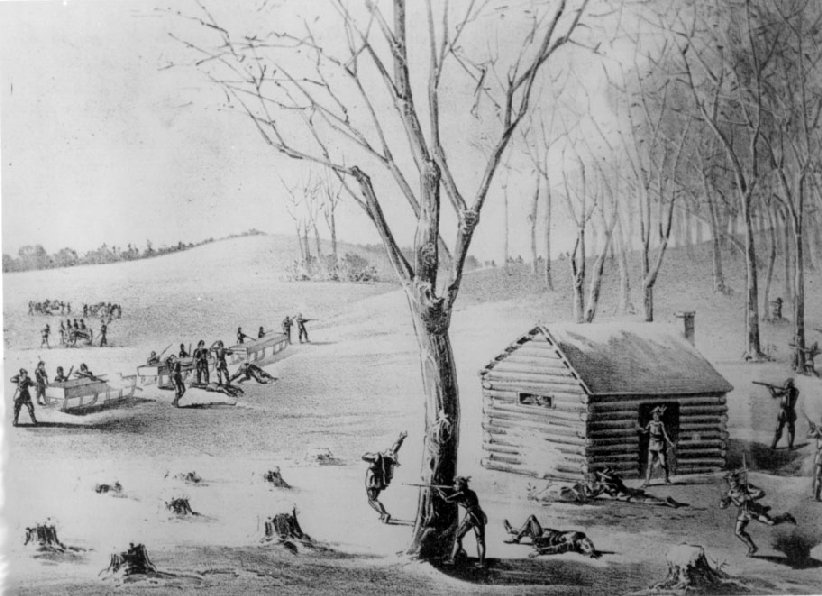

Gabriel Dumont was appointed the military leader for the rebellion while Riel would be the political leader. Riel and Dumont sought to occupy a fortified area to become their headquarters (as was the case in Manitoba). The prairies had changed and the forts of the North West were now garrisoned by the well trained and equipped North West Mounted Police (NWMP). When Dumont approached the NWMP fort outside of Duck Lake the garrison refused to surrender. Fearing a siege, the commander sortied a force to travel to a local store for supplies. This sortied force of NWMP was ambushed by Dumont and his forces. After a short battle both Metis and NWMP lay dead. This violence against official agents of the crown would change the character of the Metis movement. Fearing reprisal many First Nation’s leaders distanced themselves from the rebellion. Settlers also feared reprisals and many also distanced themselves from the movement. What had begun as a united political resistance movement was now an isolated violent rebellion.

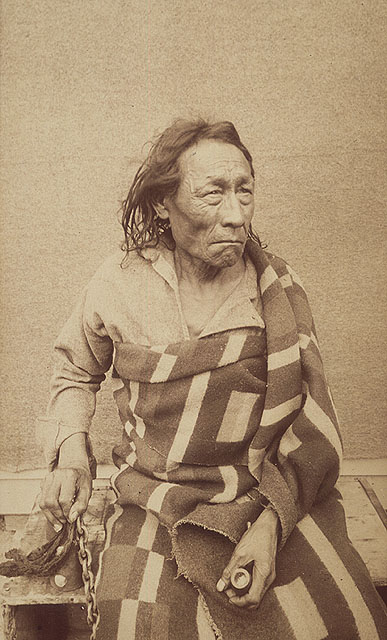

Fearing reprisal against First Nations for originally supporting the movement, Chief Poundmaker would lead his band to Fort Battleford to seek more rations, pledge their loyalty, and generally become visible to the NWMP in the fort. The townspeople in Battleford believed that the arrival of the large group under Poundmaker was part of the rebellion and fled. Some violence erupted between the townspeople and some of Poundmaker’s band who would loot the local store and houses for food. In response to the violence, Poundmaker took his people further north away from the community.

Meanwhile in the community of Frog Lake, Cree warriors from Big Bear’s Band attacked the local settlement at Frog Lake. Big Bear believed that the Metis Rebellion could offer the opportunity to renegotiate treaties that were failing his people. The attack on the Frog Lake HBC store was led by War Chief Wandering Spirit to access supplies for the starving Cree peoples in the area. Wandering Spirit would also take the local Indian Agent named Thomas Quinn hostage believing that he was responsible for withholding needed rations and starving the local indigenous peoples. When Quinn and local priests refused to become hostages, they were executed by Wandering Spirit against the objections and attempted intervention of Big Bear. In total, 9 were killed and 70 were taken hostage.

Aided by the nearly completed railway, the Canadian government under MacDonald was no longer forced to negotiate and formed a large army under Major General Middleton. To MacDonald, this rebellion would be a major test of Canada’s ability to show control over the prairies – there was a deep fear of American annexation which would split the new country of Canada in half. This powerful force included artillery, infantry, calvary, the NWMP and even gatling guns. This force was tasked with securing the entire North West and flushing out the rebels. The center of power for the Metis rebellion was in the Batoche area in what would become Saskatchewan; however, the Canadian force would split into three subsections to secure the entire North West.

A column under the command of Colonel Otter, was sent to relieve the town of Battleford which had taken shelter in the local NWMP fort after the arrival of Poundmaker’s band. Otter found the town abandoned and the fort garrisoned with local militia and NWMP while Poundmaker’s band had left the community long ago after looting local stores for food. Ignoring orders from Middleton to stay and to garrison Battleford, Otter pursued Poundmaker’s people to their reserve. Finding the Cree and other Assiniboine at Cut Knife Creek (where they had gathered in strength to wait out the rebellion), Otter ordered an advance with his nearly 400 men along with artillery and a gatling gun. Otter was quickly overwhelmed by Cree and Assiniboine in the camp and was forced to order a retreat after 6 hours of hard fighting. It was only the intervention of Poundmaker that stopped warriors from pursuing the fleeing Canadians on horse back and routing the force. 14 Canadians were wounded and 8 were killed while estimates put the death toll among Poundmaker’s people at 5 dead and 8 wounded. This incident, as well as the looting of Battleford would be used to put Poundmaker on trial at the conclusion of the Rebellion and find him guilty of participating in the Rebellion. In 2019, the Canadian government would pardon Poundmaker arguing that history had shown he was caught up in a situation beyond his control.

The main Canadian force under General Middleton himself would engage the bulk of the militant Metis at Batoche. This action would become the decisive battle of the rebellion. Batoche had become the ad hoc capital of the Metis state and the center for all military and legal efforts that made up the formal rebellion. Middleton would use his manpower advantage to encircle the Metis capital. The Metis, under Dumont’s leadership, had set up firing pits and trenches to support their defenses. Supported by artillery and gatling gun fire, the Canadian infantry closed their encirclement. The battle would last over three days with fighting taking place from distance due to the marksmanship of the Metis and the Canadian forces. Middleton was a cautious commander who sought to reduce casualties seeking to avoid the bloodshed seen in the United States. After the first day, Canadian troops would withdraw and create their own hasty fortifications around the settlement. Middleton’s artillery would prove decisive in the battle. On May 12th, 1885, the Canadian forces stormed Batoche. By this time the Metis were low on ammunition and their morale was low from constant bombardment. Without orders from Middleton, the Midlanders, 90th Winnipeg Rifles and the Royal Grenadiers charged the town. It is unknown who gave this order. Seeing the Metis in panic, Middleton ordered a general charge into the settlement. After a determined three-day resistance, the defenders would surrender. This defeat effectively ended the rebellion with Riel himself being captured.

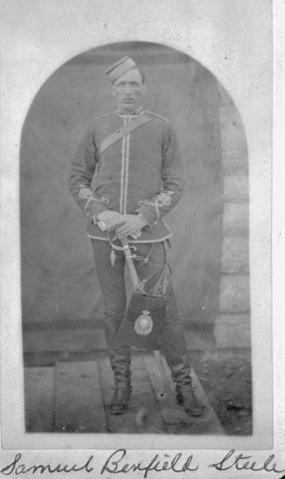

The last of the three columns would engage Cree under Big Bear at the Battle Frenchman’s Butte. This column known, as the Alberta Field Force was led by retired British Major General Thomas Strange. The Alberta Field Force would also include a substantial part of the NWMP led by Major Same Steele. The Alberta Field Force would fall upon a Big Bear’s Cree band led by War Chief Wandering Spirit, resulting in a violent struggle. Although the battle would allow time for the majority of Big Bear’s band to flee it was a pyric victory as at by the time of the battle the Metis had already surrendered at Batoche and Poundmaker had already turned himself in. Big Bear would later turn himself into Canadian authorities where he would be convicted as organizing a rebellion against government authority.

With the rebellion now over, Canada had secured complete control over the northern prairies. Riel would be put on trial and hanged for treason, Dumont fled to the United States, Poundmaker and Big Bear were sentenced to prison terms that would hasten their deaths. Wandering Spirit was hung along side 8 other indigenous leaders. The rank and file of the Metis (and those settlers and first nations that participated) were granted amnesty. The trials and executions would divide Central and Eastern Canadians. The Canadian government would not address the causes of the rebellion, and little changed between the adversarial relationships on the prairies. Middleton had successfully exerted Canadian control over the North West with little losses compared to the bloody campaigns plaguing the United States. Canadian units that fought in the rebellion included the: 12th Manitoba Dragoons, Canadian Fusiliers (City of London Regiment, Governor General’s Foot Guards, Les Voltigeur de Quebec, Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, Royal Canadian Dragoons, Royal Canadian Regiment, Winnipeg Light Infantry, 91st Winnipeg Battalion of Light Infantry, Manitoba Grenadiers, Alberta Mounted Infantry, Boulton’s Mounted Corps, Fusiliers Mont-Royal, Halifax Provisional Battalion, Midland Provisional Battalion, Moose Mountain Scouts, Prince Albert Volunteers, Rocky Mountain Rangers, and the North West Mounted Police.

Our museum showcases the type of uniform worn by North West Mounted Police units that would form part of the Alberta Field Force during this conflict.

Bibliography / Further Information

Government of Canada, National Archives of Canada. “Battle of Fish Creek, North West Rebellion.” Archived – battle of fish creek, North West Rebellion, 1885, by Fred Curzon – the Canadian west – exhibitions – library and Archives Canada. Accessed June 17, 2025. https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/canadian-west/052920/05292031_e.html.

“Item A16340 – Samuel Benfield Steele.” Searchprovincialarchives.alberta.ca. Accessed June 17, 2025. https://searchprovincialarchives.alberta.ca/samuel-benfield-steele.

“The History of the North-West Rebellion of 1885: Comprising a Full and Impartial Account of the Origin and Progress of the War, of the Various Engagements with the Indians and Half-Breeds, of the Heroic Deeds Performed by Officers and Men, and of Touching Scenes in the Field, the Camp, and the Cabin: Including a History of the Indian Tribes of North-Western Canada, Their Numbers, Modes of Living, Habits, Customs, Religious Rites and Ceremonies: With Thrilling Narratives of Captures, Imprisonment, Massacres, and Hair-Breadth Escapes of White Settlers, Etc. : Mulvaney, Charles Pelham, 1835-1885. (Author) : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, January 1, 1885. https://archive.org/details/P001508/page/n11/mode/2up.