The Great War 1914 – 1918

What will become known as the Great War (also as World War One after the start of World War Two) was caused by a variety of factors. Great power competition among industrial powers (and their empires) had created a situation where several empires actively sought war. The spark that would ignite the conflict would come from the assassination of Archduke Frans Ferdinand, of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, who was shot while on a visit to neighboring Serbia. This assassination at the hands of a terrorist group known as “The Black Hand.” “The Black Hand” sought to reduce the influence of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Serbia. The assassination of Frans Ferdinand set a series of events into motion that would set off the Conflict. Let us quickly examine these.

Industrialism: Since the industrial revolution of the early 19th Century, Europe had become reordered politically. Former “great powers” like Russia, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire had prior to the industrial revolution held sway over large areas of Europe and were influential due to their large manpower advantages and autocratic governance models that required service from their subjects. The technology of the industrial revolution would see repeating firearms and advanced munitions that would negate traditional manpower advantages. The industrial revolution relied on coal, raw materials, factories, an urban working class, and a culture of invention and experimentation that overcame the organizational prowess of autocratic absolutism. States and empires like the British, French, and the newly united Germany would now (through industrialism) be able to overcome the manpower advantages of empires in decline. For the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, those in power sought a war to unite their people under their rule and to stave off the weakness of their economies and the ethnic divisiveness of their empires. Industrialism also allowed nations like Germany to challenge traditional powers like Britain for naval supremacy. This challenge for naval supremacy would stoke tensions between Britain and Germany leading to the Canadian Naval Crisis (where Britain asked Canada to finance the construction of royal navy warships) that would topple the Laurier government.

Nationalism: would play a key role in the origins of the Great War. Nationalism sought to unite people together who shared a sense of culture, identity, and history, under a shared worldview or state. Nationalism had become unleashed on Europe during the later half of the 19th Century with new nationalist states like Germany and Italy being formed out of ancient trans-national principalities. Nationalism united together people in states with shared identities like Germany and France while dividing and sowing discord in transnational states like Austria-Hungry and the Ottoman Empire which were made up of dozens of competing ethnicities and languages. Nationalism sought to subvert individual identities and cultures to a shared experience and history that would govern the worldview of the state. Nationalism is by its nature competitive and exclusionary. If one believes that their nation and their people are superior to all others, then they are also speaking negatively about all other nations. It is this nationalism that would be the driving force that would encourage states to seek conflict, view others as week, and stoke tensions in transnational empires. States like France who had lost a war to Germany in 1871 and Russia who had lost a war to Japan in 1905 were eager to prove themselves, and their national identity, in another conflict.

Empire: would also play a major role in the origin of the Great War. Great industrial states like Britain and France would have their power amplified by large non continuous empires that spanned the globe. These empires would provide (often without choice) access to large deposits of raw materials that were necessary to fuel industrialism, food to offset the urbanization of their populations, and markets for the selling of completed industrial goods. Throughout most of these empires the concepts of imperialism had taken root. Imperialism sees one sovereign states exercise dominance and control over another sovereign state. Under and imperial framework parts of the world become dominated by a European power yet are denied citizenship and legal protections since the dominated people by technicality only remain independent within the greater empire. Newly forced nation states like Germany and Italy would find most of the non-European world already divided up the other great industrial powers. Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany believed that German’s place in the sun would be found by initiating conflict with other European powers with the goal of extorting colonial possessions to fuel the German Empire.

Baring all these concepts in mind it is easy to see how a general European war can be seen as inevitable. Due to the increased tensions throughout Europe in the period leading up to the war, great powers began to seek alliances and cooperation to contain their shared enemies. France, Britain and Russia would unite to form the Triple Entente which was tasked with containing the power and spread of militaristic Germany. The Entente was weakened due to mistrust between all three members who had long histories of conflict among each other. Germany would form the Triple Alliance between Germany, Italy and Austria-Hungary. The alliance was aimed to mutual support in times of war, although Italy and Austria-Hungry struggled economically and industrially. It was this series of alliances that would set in motion the start of the conflict.

When Frans-Ferdinand Archduke of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was assassinated by Serbian nationalists, Austria-Hungry attempted to bully tiny Serbia into subservience (seeking a war to unite its transnational empire), however Russia under Tsar Nicholas II believed that Serbians who shared language traits (key parts of a nationalist identity) with Russians needed to be protected and declared that any attempt to invade Serbia would see Russia come to Serbia’s defense. Austria- Hungry would likely struggle in a war against the larger Russia, so Austria-Hungry asked for support from its Triple Alliance members of Italy and Germany. Germany pledged immediate support to Austria-Hungry in their potential fight against Russia. Italy, realizing that its interests lay in reclaiming Italian speaking lands from the Austro-Hungarian empire decline to support their neighbour. Germany now planned for a fight against Russia and potentially their entente allies. Britain as a global power that simply sought Germany to be limited offered economic support but pledged general neutrality, France openly followed a similar policy. However, historians have been able to access archival materials that show France as planning to directly invade Germany, but only once German military forces were already committed against Russia. France sought to reclaim Alsace Loraine which had been lost to Germany in their war in 1871. Germany knowing that it was likely that France would attack once committed against Russia made a bold move. Instead of mobilizing its vast armies directly against Russia, Germany would attack France pre-emptively using the Schlieffen Plan. German leaders theorized that it would take upwards of 16 weeks for Russia to recruit, train, and equip a military force that could go on the offensive against Germany and Austrian-Hungry, it was hoped that through careful planning and overwhelming force that France could be defeated before Russia could mobilize thus ending the fear of a two-front war.

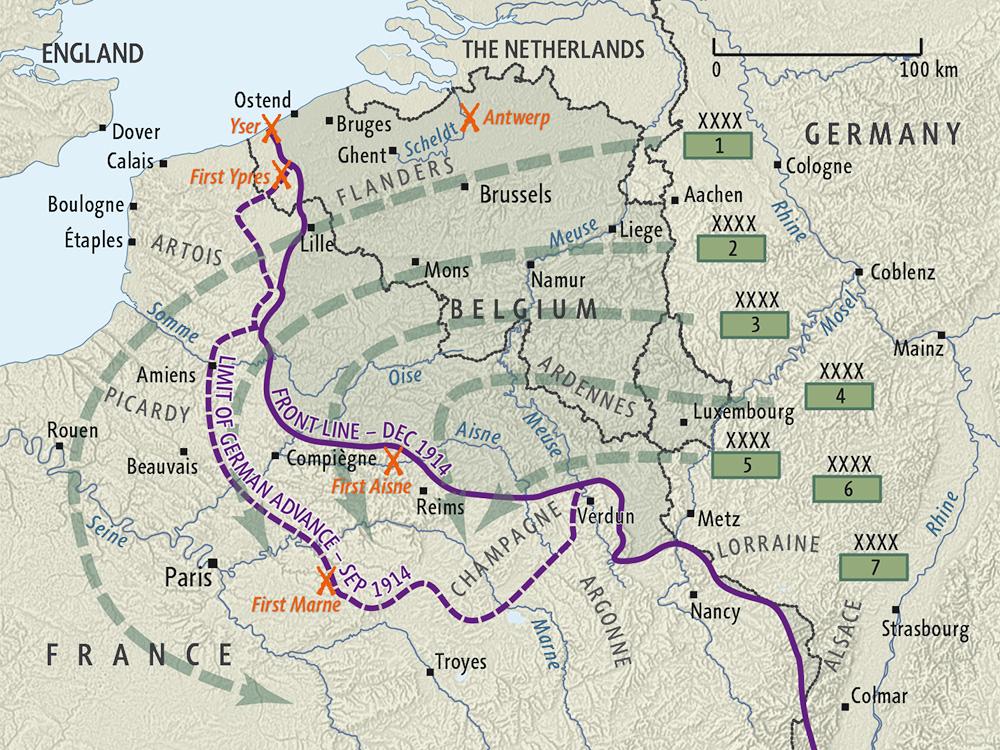

The Schlieffen plan sought to attack France not directly, as expected through the shared Franco-German border, but instead through neutral Belgium. Belgium’s neutrality had been guaranteed by the British Empire going back to the end of the Napoleonic Wars. German leaders believed that Belgium’s King Albert and his small army would immediately surrender when faced with the overwhelming force of the German armies. However, Belgium decided to fight knowing that it would receive support from the British and the French. Belgium destroyed its rail network and placed its meager forces into strongly fortified positions to fight a delaying action. The arrival of the small but well trained and equipped British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to Belgium would also slow the German advance. German war planners began to worry that their advance although powerful and nearly unstoppable was taking too long. Their fears were confirmed when a Russian force attacked eastern Germany after only a week. With troops being slowed by the BEF, France and Belgium in the West and the need to draw experienced troops eastward, the German offense would stall at the Marne River outside of Paris and a war of ridged defense would ensue.

At this point Canada would as part of the British Empire enter the conflict. By 1914 Canada had only achieved a quasi-independent status and was subservient to British foreign policy. Like the experience of the Boer War, Canadian support for the conflict varied by identity with those who saw themselves as British supporting the conflict more passionately than those who identified as Quebecois. The make up of the Canadian army would reflect their as its structures, language conventions and officer corps were nearly exclusively English. Only one regiment the Royal 22nd was a majority French unit. Eager to showcase itself as important to the British Empire, Canada would contribute large units of men to the war effort with thousands of volunteers joining the ranks of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). The Canadian navy would be transferred to British control under agreements formed after the toppling of Liberal Prime Minister Sir. Wilfred Laurier’s government years earlier.

Prime Minister Borden would appoint Sam Hughes as the Minister of Militia. Hughes would raise and equip new units. Hughes an ardent British nationalist initially looked to limit participation of French Canadians, Indigenous peoples and racialized minorities in the Canadian war effort. These limits would only be rescinded when by 1917 volunteerism declined nationally and new sources of recruits were needed. Hughes would also look to equip Canadian soldiers with supplies and gear sourced from Canada to keep supply lines and increase national industrial output. Contracts were at times awarded for equipment based on social connection rather than quality. This led to complaints from Canadian soldiers about the inferior quality of equipment. The Ross Rifle, chosen by Hughes became a lightening rod for grievances with soldiers writing home complaining about the rifles ability to function in combat conditions and in the mud of the trenches. Although not a bad rifle the Ross was not designed with the muddy trenches of Flanders in mind and was also originally chambered in a unique proprietary cartridge which had been substituted for the standard .303 British bullet, these factors led to an often malfunctioning yet innovative rifle. Hughes’ ignoring of pleas from service people would contribute to his downfall when he was dismissed as Minister of Munitions by Prime Minister Borden. The Ross rifle would be immediately replaced with the British Lee Enfield SMLE. The museum proudly displays both the Ross and the SMLE in our armoury.

After the failure of the Schlieffen plan, the Great War would become dominated (at least in the West) by hundreds of kilometers of trenches dug into the landscape that would stretch from the neutral Swiss border to the English Channel. This style of fighting would put technological innovations that aided the defender against tactics that had yet to evolve leading to massive wave attacks that killed at times tens of thousands and men daily. The war had become static. New inventions like aircraft, tanks and poison gas would be developed and militarized in hopes of breaking the stalemate however these were quickly countered leading to a general tone of senseless death and destruction. Although rarely used poison gas would have a major psychological effect on soldiers on both sides who feared a horrible death from the coloured gasses used by both sides to clear the trenches.

In Canada, the need to fabricate massive amounts of ammunition and equipped would centralize our industrial economy in Ontario and Quebec and would see a drastic readjustment of our national workforce to urban centers. With the considerable number of young men drawn into combat arms, women, children, and first nations were called upon to increase production in Canadian factories and work on Canadian farms. Those at home were asked to ration their purchases to ensure that there was enough raw materials and food to fuel Canada’s war effort.

Early in the war, Canadian units were used piecemeal within the allied lines as reinforcement to spent British units. The bloody Battle of the Somme would see Canadian units committed in large numbers to overwhelm German defenders. Although there were successes, overall, the battle would end in a bloody massacre with over 60 000 allied soldiers perishing with little to gain.

It was after bloody battles like the Somme that Prime Minister Borden would push for Canadian soldiers to be reformed into a unique Canadian army under Canadian command and responsible to the Canadian parliament. Due to the situation at the front, and the British need for Canadian participation, Canada would be granted the ability to form their own unique army group commanded by General Arthur Currie. Under General Currie the Canadians would gain a reputation as hard fighting and brave while seeing unexpected success at the Battle of Vimy Ridge, Aras, Amiens and Passchendaele. In 1915, the Canadian Corp would number approximately 35 000 men in 1915 but would balloon to over 100 000 combat troops in 1917. In total over 650 000 Canadian enlisted for service with 424 000 serving overseas.

Canada would struggle to keep up with the losses to its now independently led army and Prime Minister Border would be forced to purse a policy of conscription to keep up with the needed recruitment. Those who had chosen not to join up in the war effort were labelled as shirkers. This created regional splinters as many in Quebec had not joined the war effort as this region had a lesser connection to the British Empire and identified with their own French “Canadien” identity. Leaders like Henri Bourassa argued that the real fight for Quebecers was at home for their language and culture rights in Canada rather than to fight the Germans. Other groups like farmers, religious minorities, and members of industrial unions had also not volunteered on mass. Conscription would force groups of eligible men to join the army or navy in service to Canada and the Empire. To ensure that the vote for conscription would pass by plebiscite the Conservative Party would unite with most of the English members of Liberal party to form the new Union government. This would make the issue of conscription less political. Non-enfranchised members of the military were given full voting rights; however, the government could apply these “overseas” votes to whatever riding they chose. Women who had family members who were serving overseas were also granted the right to vote as they were seen as more likely to support conscription as it may lead to exhausted troops returning. Conscription would pass although nationalists in Quebec were angered at the process. Ironically, the war would end before many of the conscripted troops even arrived in Europe.

George Metcalf Archival Collection

CWM 19930003-556

CWM 19760586-002_8

Eventually the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungry and their ally the Ottoman Empire would collapse under the weight of the prolonged conflict. The world would be forever changed and reshaped by the Great War. Russia would collapse due to the losses and economic issues it faced during the war and would emerge from a bloody civil war reborn as the Soviet Union. After the sinking of a passenger vessel by German submarines, the United States of America would join the war in 1917. The Treaty of Versailles that ended the was would divide up parts of the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires into dozens of smaller nation states. Germany would be demilitarized and forced to become a democracy known as the Weimer Republic once all Imperial Germany’s leaders fled. Canada would see its prestige rise on the international stage with a new global influence won in the trenches. By the middle of the 1920s, Canada would use their increased global influence to gain control over its own foreign policy and be seen as an equal to England within the British Empire.

It is for these reasons that historians say that Canada was born, as a unique and independent country, from the blood of the trenches of the Great War. The museum has on display artifacts from this conflict including uniforms, helmets, firearms, gas masks, and personal memorabilia from the conflict. Come browse the collection and examine the physical history of this defining conflict.

The uniform on display represents the uniform worn by Canadian soldiers who served in the conflict and belonged to Company Sergeant Ira Milner with the 1st Battalion Royal Canadian Regiment. Several helmets, gas masks, photos, letters, and war trophies are also on display.

Kevin Rodgers, Curator